Wilder in the Streets

Losing yourself in 'Times Square' and other elsewheres

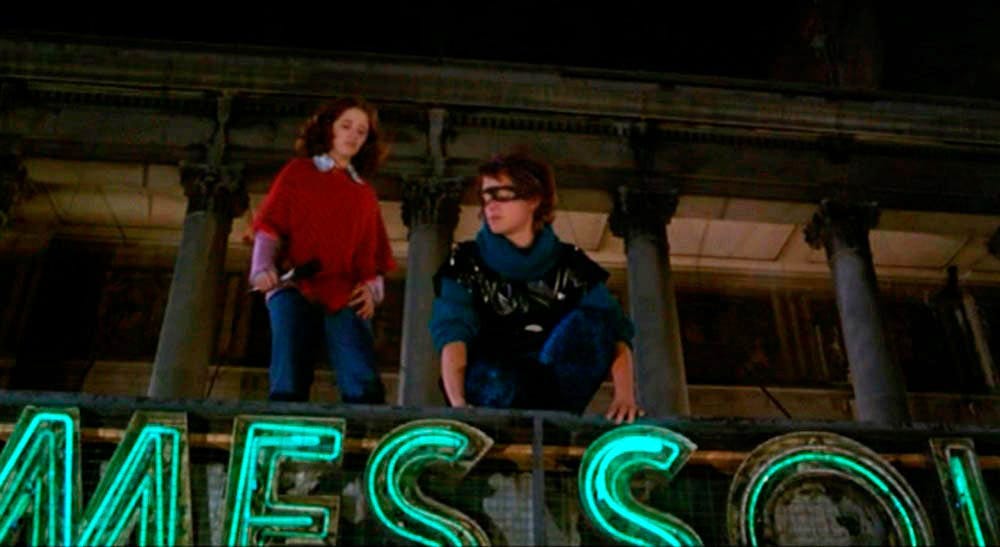

In the darkness that opens Allan Moyle’s 1980 film, teenage Nicky Marotta (Robin Johnson) drifts through the vibrant nightlife in titular Times Square, while members of a diverse New York crowd sway to Roxy Music’s “Same Old Scene.” Some take notice of the young girl, who moves with intention, left alone (like everyone else) to do her own thing. Nicky finds a perch and begins playing distorted guitar chords, purposefully renouncing that precious city dweller anonymity and getting herself arrested.

Meanwhile, under a banner that reads “Reclaim Restore,” David Pearl (Peter Coffield), a prominent city commissioner, speaks to a half empty room about the need to clean up Times Square. He recounts an argument between himself and his 14-year-old daughter Pamela (Trini Alvarado) over permission to see a movie in the neighborhood, concluding with the clever: “While I didn’t mind the R-rated film, I objected to the X-rated community.”

Shaking her head and muttering, “It’s not true,” Pamela storms out of the speech, resenting her role as fictional bit player in her father’s political theater.

Nicky and Pamela soon meet sharing a room in a hospital, where they are both being tested for an unnamed brain disorder (both show unmistakable signs of rebellious teenage girl syndrome). Recalling Linda Blair’s “What’s wrong with me?” from The Exorcist, Pamela asks, “Am I going crazy?” while watching her roommate chew the petals off a rose behind their doctors’ backs.

Nicky blasts The Ramones’ “I Wanna Be Sedated” from her boombox, setting up a punchline that later lands when David Pearl first encounters the troublesome teen, asking, “Shouldn’t she be sedated?”

More humor is mined from the doctors themselves, who administer various absurd linguistic tests to determine whether there is anything medically wrong with the girls.

Nicky refuses to repeat the term “Methodist Episcopal.” When asked to explain the adage “out of the frying pan and into the fire,” Pamela responds, “It’s where you go when you don’t want to be eaten for dinner.”

Like recognizes like and the two steal an ambulance and end up living together on an abandoned pier. There is magic in their escape, at least for the film’s euphoric first half. Time Out called Times Square: “socially irresponsible and refreshingly optimistic: a Wizard of Oz for the ‘80s.”

Supposedly based on the diary of a mentally disturbed young woman Moyle found in a second-hand couch, the films starts as a fairy tale, but goes sour when Nicky is overwhelmed by her mental illness. Her behavior looks manic: the highs very high and the lows brutal.

Times Square’s first half has a markedly different rhythm from its ending, which becomes nonsensical and choppy after Nicky’s behavior suddenly changes without any apparent motivation.

You can feel the unresolved struggle between producer Robert Stigwood, seeking to duplicate his Saturday Night Fever film/soundtrack crossover success, and Allan Moyle, the director who was forced to remove some overt lesbian content and add inappropriate songs to fill out the score.

(The film that made John Travolta a superstar, Saturday Night Fever had a huge cultural impact upon its 1977 release, bringing New York’s disco dance and fashion subculture to a mainstream audience. Still one of the highest-grossing R-rated films ever made, the film’s double album soundtrack was even more successful, becoming the best selling album in music history prior to the release of Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Using another gritty New York night life film as vehicle, Stigwood’s two-disc Times Square soundtrack attempted (to little avail) to do for punk and new wave what Saturday Night Fever accomplished for disco.)

Moyle left the film before it was completed; its conclusion’s shift in style and perspective provides evidence of the departure — a ship gone aimless with no one at the helm. The effect is very similar to the last ten minutes of The Magnificent Ambersons, Orson Welles’ lost masterpiece, which was famously butchered by a studio that didn’t understand what the film was about.

Times Square’s poetry appears as the two girls quickly form a close relationship, and are comically seen pulling off a number of scams for money on the city’s famously mean streets. Their devotion to one another is lushly romantic, a chaste “you and me against the world” love story told with an ardor only teenagers, for whom so many emotional attachments are firsts, can access.

In one particularly exuberant scene, the girls dance down a crowded sidewalk at night encouraged by the man following them, whose boombox blasts Talking Heads’ “Life During Wartime.” As they choreograph moves, other dancers join in, following their steps while joyously adding flourishes of their own.

Eventually -- and unbelievably -- Pamela gets a job dancing at The Cleopatra, a seedy topless bar, where she refuses to go without a top, but nonetheless generates income and applause.

The bar magically transforms into a punk hangout when Nicky performs “Damn Dog” as her rock star alter ego Aggie Doom with the house band. (”I can lick your face. I can bite it too. My teeth got rabies. I’m gonna give ‘em to you.”)

As is true in other teen films, adult denizens of the bar’s alternative subculture assist the underage girls in their emancipation, providing access to inappropriate spaces and activities so the teens can support themselves while evading their parents and the law.

With the help of Johnny LaGuardia (Tim Curry), a local DJ who opposes David Pearl’s Times Square clean up campaign, Pamela (also known as “Zombie Girl”) sends messages to her dad over the radio. In one instance, she exposes his racism and homophobia in song: “Spic, Nigger, Faggot, Bum -- your daughter is one.”

The girls, now known as The Sleez Sisters, develop a following, but their harmless pranks become more dangerous when they begin dropping TV sets onto the crowded sidewalks from the tops of buildings, narrowly missing pedestrians going about their daily business. Many great images of falling televisions reflect the anti-television times. One such shot tracks a white plastic portable down the side of a building while Tim Curry’s DJ intones: “Apathy. Banality. Boredom. Television.” Smash.

He encourages the girls’ dangerous rebellion: “Let it be passionate -- or not at all.”

But at this point, the film itself starts to crash. The style becomes much less effusive and the storytelling gets muddled. The two girls exit their fairy tale and begin to separate. Pamela realizes she’s not as extreme as Nicky and must return to the safety of her privilege, which forces Nicky to understand that she is essentially alone -- attractive, charismatic, creative, commanding, and alone.

I have been Pamela and I have been Nicky, too.

The film concludes with a final fantasy. Nicky and Pamela put on a midnight concert in Times Square, drawing a crowd of teenage girls dressed in garbage bags, inspired by Nicky’s uniform. “If they treat you like garbage, put your body in a garbage bag.” Performing on top of a sleazy movie theater marquee, the police charge Nicky mid-song and she jumps, but is enveloped by the girls, who aid her escape.

I wonder if this is where I first began developing (eventually destructive) ideas about what passion, inspiration, and creativity looked like. Many of the artist warrens I would later encounter resembled the cluttered quarters that Nicky and Pamela assembled for themselves in an empty apartment over the pier. Many of the people I would find myself most attracted to were as unpredictably edgy and often as certifiably insane as Nicky.

My closest friend the year Times Square was released — my first true best friend — was a whip-smart, extremely talented, but dangerously mercurial kid who inexplicably befriended me in the middle of my sophomore year of high school. My feelings were similar to others in a small group of misfits that coalesced around this charismatic character: The sun shined when he recognized you. He was so witty and inventive that his acknowledgement conferred more real validation than you were likely to receive elsewhere. But you could quickly be left in the cold when he chose to withhold his attentions, delivering first a sharp rebuke with a notoriously acid tongue, and then cutting you out of conversations and activities for undetermined periods.

He was able to evade most of my defenses, showering attention on the barren wasteland of my teenage social life, encouraging new ideas to grow where rote concepts had struggled into spindly existence. I saw myself in a new light, through the eyes of another person who began by affirming my intellect and creativity, then later expressed discomfort at my closeness, my hero worship.

When I first met him, my dreams were all received from family, primarily located in or in close proximity to the small town where we all grew up. There seemed to be a force field that extended perhaps thirty miles in every direction. My life was proscribed by this circle. While my earliest memories are of my mother insisting I would go to college, the state school she had in mind and the one I understood I would attend was a mere thirty miles south. I could live at home while I got my education. My freedom would be importantly monitored and curtailed.

But my new best friend had different dreams. He was hellbent on escape. He had his sites on U.C. Berkeley. And then suddenly so did I. And then I got accepted and then I won a scholarship to attend. My world opened up because this boy showed me that it was bigger than I had, up to that point, imagined. He made me realize my life could be bigger, too.

When I went to Berkeley, he attended the San Francisco Art Institute, once again demonstrating that he was the sun and I was merely a satellite. I didn’t know what I wanted to be, but my choices remained safe. His were gonzo fuck all, no hedging of bets.

And then something happened to him and he disappeared, suffering a real break with reality. There were medications that made his weight fluctuate and his mood stabilize and his mind grow calm, and the sun go dim.

I understood that I was Pamela to his Nicky. He could and would throw himself over the edge, but that was an ability I would never possess. I could accompany those who ran quickly toward the horizon, and remain comfortable much closer to the brink than most, but I would always pull back and protect myself while people I loved continued into the void.

My high school best friend wouldn’t be the last person I lost forever. Others would spectacularly enter my life, volume at 11, light too bright, colors fully saturated, and then, often just a short time later, they would tragically depart, leaving smoke behind, a world rendered in shades of burn-out gray.

Just as overt homo content was left out of Times Square, I wonder if the same has been edited from my memories of our teenage relationship. We never engaged in activity that even remotely approached the sexual or the intimate, but I wonder if he wasn’t my first crush and I just didn’t realize it at the time. One’s blind spot is by definition a place one is unable to see into.

He had a massive influence on my thinking, encountering a genuine sleepwalker and choosing to shake me awake. Why, I will never know. He demonstrated how an alternative existence could be imagined and brought to life. I still owe so much of who I later became to him, but I wonder if my deeply repressed sexuality ever manifested itself in a way that I was not conscious of, forcing him to repeatedly abandon our friendship.

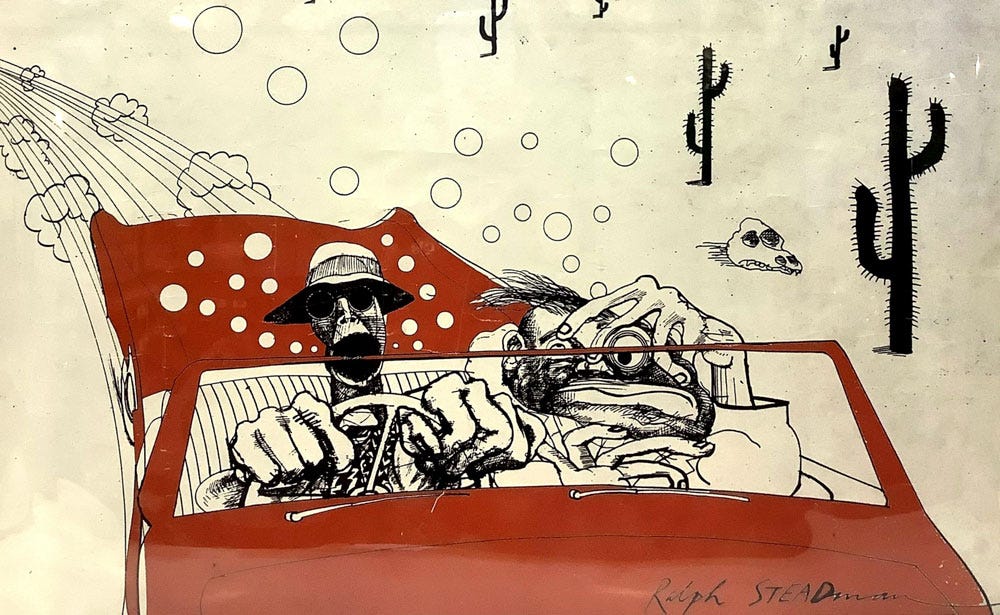

Teens have their own problems, and one of his was the sudden desire to just randomly blow shit up, especially his own life. Throughout the last years of high school, we consumed a boatload of chaos-exalting media. Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas became our foundational text, inspiring a similar search for excess, though indiscriminate drug consumption proved difficult to accomplish while living in a small-town fishbowl. The radical politics of Gang of Four and Dead Kennedys played incessantly out of our car stereos on road trips to see other bands, Flipper, Wall of Voodoo, X.

To fulfill an Honor’s English requirement, we performed Macbeth multiple times in various classrooms, initially to loser sneeze jeers of “faggot” and eventually winning cheers at the humor mined from every high schooler’s least favorite playwright. We memorized the whole text and recited it so fast, our performance clocked in at a little over 40 minutes. He played Macbeth, standing in the middle of the stage, reciting lines while gesturing like a cartoon king, left or right arm extended to the heavens. I performed all the other characters, a whirlwind circling him in various costumes and battling myself to the death.

That picture is pretty accurate: one of us standing still, confident in his own skin; the other swirling, becoming as many different people as possible in search of an acceptable identity.

He helped me construct the armor I needed to finally ignore whatever snide slurs were hurled my way. I learned not to give a fuck what the idiots in my high school thought of me. I no longer needed to be invisible, because I didn’t care about the people looking. I was already seeing past those assholes to some other place, a better future where they had long faded from consideration.

I eventually developed into a version of Times Square’s Nicky, able to cast my own glamour, to make my environment more colorful through creativity, charisma, and force of will — along with a hair-trigger urge to break things, especially me.

Like a Ralph Steadman ink explosion, I often imagined myself sun-glassed and big-headed in a car racing away from a town on fire.

No looking back.

Things get even wilder next week.

EVEN WILDER next week? Heaven preserve us. I appreciated the influence of Times Square on your own life and art. Question: whatever became of Robin Johnson??? Comment: wow, Trini Alvarado was REALLY YOUNG in this film!