Wild in the Streets

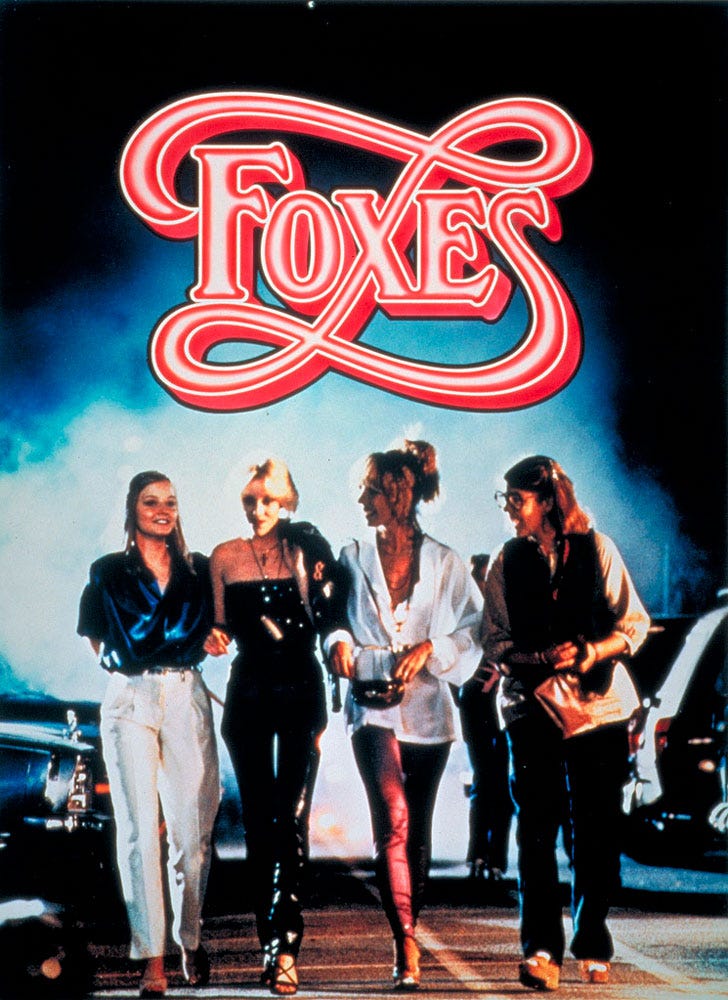

'Foxes' seeking teenage kicks in the late seventies/early eighties

Set in Nixon-era Connecticut, Ang Lee’s 1997 film adaptation of Rick Moody’s The Ice Storm bristles with 1970s angst, brilliantly skewering “Me Generation” parenting. While the adult characters test the limits of suburban social strictures through drugs, alcohol, and adulterous sex, their kids begin similar experiments, reflecting their parents’ uncertainty about received norms and practices.

In a particularly hilarious scene, Janey Carver (Sigourney Weaver) discovers her pre-teen son, Sandy (Adam Hann-Byrd), playing an uncomfortable game of I’ll show you mine if you show me yours with Wendy (Christina Ricci), the slightly older daughter of neighbor, Ben (Kevin Kline), with whom she is having an extra-marital affair. In reaction to this awkward sexual experimentation, Janey places her hands on the young girl’s shoulders and intentionally maintains eye contact while attempting to provide Wendy with much needed adult guidance.

Janey’s gibberish neither addresses the current situation, nor does it offer any real advice about sex and sexuality. The cursory information about third world coming of age rituals feels like it was gleaned skimming a magazine in a doctor’s office. The scene demonstrates both Janey’s uneasiness about parenting and her confusion over the values she would or should transmit. Her own experimentation and conflicted attitude toward social mores infects her judgment as an authority figure; she no longer trusts her moral compass and can offer little wisdom to the children in her community. Her compulsion to do so feels performative, an automatic response to imaginary stimuli from a phantom limb.

A similarly nonsensical interaction occurs in Adrian Lyne’s 1980 film Foxes, about a group of four teenage girls who party their way through adolescence on the streets of Los Angeles. Jeanie (Jodie Foster) and her mother Mary (Sally Kellerman) get into an argument after Jeanie’s friend Annie is committed to a mental hospital. Mary suggests asking Annie’s doctors for their opinion on her condition, but Jeanie doesn’t trust them -- or anyone over twenty -- to provide an honest opinion.

The scene ends with a close up of Jodie Foster’s tear stained face. She has the look of a latchkey kid who has become a parent to her own mother, simultaneously loving, empathetic, and disappointed. Jeanie is forced to face her burden alone; her hope for guidance and support effaced (once more) by Mary’s self-doubt.

The girl is becoming a young woman, exercising her own brand of female power, which challenges the model that came before, multiplying the older woman’s questions about her own place in the world. What begins as a fight over a crisis in the daughter’s life ends as an expression of the mother’s insecurity, illustrating how few boundaries exist between adult and child.

Both Foxes and The Ice Storm depict adult confusion as contagious; uncertain parents echoed and amplified by morally ambiguous children. The latter is a parody of the former. Made in 1997, The Ice Storm details an absurdly cold extreme of social experimentation and self-involvement that severs adult and child worlds, making them into distorted mirrors of one another. The film recalls the style and substance of parental bewilderment in seventies cinema, epitomized by Kellerman’s Mary in Foxes, haphazardly attempting self-actualization by pursuing a college degree at 40, and apparently looking for love in all the wrong places (a phrase popularized by the hit country song that dominated the airwaves when the film came out in 1980). In her mind, Mary’s quest is meant to improve possibilities for both herself and her daughter. This belief was true off screen as well.

The era’s popular wisdom declared the best role model for children was a parent focused on self knowledge and self improvement, hence the “Me Generation” label. If these personal pursuits required more adult “me time” and resulted in fewer hours spent parenting, the example of a happier, more fulfilled, and well-rounded individual would provide the positive prototype kids needed to inform their own personal growth.

Parents had to continue working while seeking educations interrupted by the arrival (sometimes unexpected, since abortion did not become legal in the U.S. until 1973) of semi-wanted children. Devoting less time to child-rearing while chasing more lucrative prospects would hypothetically result in improved opportunities for the whole family. Latchkey kids picked up the slack, spending more time unsupervised and taking on household responsibilities with the hope of future rewards, which were often only enjoyed by younger siblings.

This utopian ideal broadly appears as “city planning” in a couple of films that appeared within a year of Foxes. Wealthy commissioner David Pearl neglects his troubled daughter while trying to clean up New York’s Times Square (1980), and nearly all the community-minded parents in Over the Edge (1979) are so focused on creating the perfect suburb, they ignore the input and actual needs of their children, and are shocked when the kids run amok.

The titular teenage “foxes” become infected with the same elusive dreams the film’s disappointed grown-ups chase, but the girls’ disillusionment arrives harder and more swiftly than it does for their misty parents. Jeanie’s dream of having her own apartment to share with her friends -- playgirl Dierdre (Kandice Stroh), frumpy Madge (Marilyn Kagan), and druggy Annie (Cherie Currie) -- mimics her rock tour manager father’s (Adam Faith) pursuit of a northern California farm/hippie hangout.

While Madge mocks her mother’s (Lois Smith) traditional values, she basically reproduces them, losing her virginity to her first true love, an inappropriately older man (Randy Quaid) who she ends up marrying.

While Dierdre’s mature adult facade seems the most convincing, her problem -- juggling the attentions of two teenage boys -- is self created and clearly adolescent.

Annie’s drug use poses the greatest challenge.

As directed by exploitation schlock-meister Adrian Lyne (Flashdance, Fatal Attraction), Foxes opens in an early morning haze, the camera lecherously focused on sixteen-year-old Jodie Foster’s bare foot and then tracking up exposed parts of her sleeping body. Drifting across the entwined limbs of Madge and Dierdre, it eventually finds Annie, who is out cold on the bedroom floor. She sleeps through the morning alarm and remains impervious to her girlfriends’ attempts to rouse her. Quaaludes are the assumed culprit. The girl eventually stirs when Jeanie splashes cold water on her face.

As personified by The Runaway’s former lead singer, Cherie Currie, Annie embodies much of that all-girl band’s infamy. The group’s original members lived fast, partied hard, ruled the world for a hot second, and then spectacularly crashed and burned, burnishing the authenticity of “Cherry Bomb,” their only major hit, which continued to echo across teen-oriented media.

Currie’s severe bleach blond feathered hairstyle was the envy of and faithfully reproduced by stoner chicks across the U.S. Her portrayal of a troubled, druggie runaway is only partially acting. According to her autobiography, Neon Angel, Currie was on uppers for most of the shoot, so that she could work on the film during the day and record an album with her twin sister Marie at night. Dealing with a formerly absent mother who showed up on set to take credit for her daughter’s success, and an alcoholic father who was in the process of drinking himself to death, Currie turned to amphetamines to focus on the film.

Everyone noticed she was looking worse for wear, but that feels appropriate for Annie, who keeps running away from her vacant mom and physically abusive policeman father, and gets committed to a mental hospital, which she escapes drugged out of her mind. In another weird echo of Currie’s own life, Annie ends up hitching a ride from a couple of swingers who become so focused on her, they plow into the back of a truck stopped on the freeway. Annie is last seen convulsing on an emergency room operating table, spitting blood into an oxygen mask.

After her departure from The Runaways, Currie recounts hitching a ride outside a Hollywood club, and ending up kidnapped, held captive, and sexually abused in a remote house on the outskirts of Los Angeles -- a scenario straight out of a seventies horror movie.

Eighteen-year-old Currie does a great job in Foxes. Her acting is wide open and vulnerable, a perfect lost cause that Foster’s Jeanie fights hard for, but cannot win. The spaced out look in Annie’s lidded eyes is a dead giveaway of Currie’s actual state.

She writes about relying on Benzedrine, slimming down to 103 pounds on the set, and wondering about anorexia. While the drug, which her teenage mind believed was legal because it was a pill rather than a powder, amped her up, she struggled with its side effects, craving Quaaludes and hard liquor, which she had sworn off in favor of pot and wine (a “healthier“ choice), to take the edge off, when she noticed a new issue:

“Looking closely, I saw something that terrified me. In the thickness of my blonde hair there were these barren patches, areas of thinness, areas of baldness. There were raised welts under my hairline, all through my scalp. I swallowed hard and stepped away from the mirror. There could only be one explanation for this. I felt in my purse and took out the vial of Benzedrine. It looked so innocent. Just a silly yellow vial. It had tricked me, I fumed, tricked me into thinking it was a harmless medicine, into thinking that it was good for me. But now, look what it was doing. I had to get off this stuff... I knew what I had to do. The solution to this problem was very clear to me. There was only one rational way to deal with it.”

“Before I returned to the set, I went to the nearest payphone and dialed the number. On the second ring, she picked up. ‘Hello Stacy, it’s Cherie.’ Stacy was a friend of mine; the one who introduced me to Benzedrine and had been supplying me with it. ‘Listen, uh, that Benzedrine stuff has been doing some weird things to me. I don’t think I should take it anymore. Can you do me a favor?’ ‘Sure, what is it?’ ‘Can you come to the set? I need you to bring me some blow,’ I said gripping the receiver very tight. ‘I need you to bring it as fast as you can.’ I hung up, already feeling better. Coke had never made my damn hair fall out. No more of that stuff for me. Nope. This is a new Cherie Currie, a responsible Cherie who would recognize when she had a problem and deal with it accordingly. Feeling highly responsible and totally in control, I strode over to the set, ready to act, ready to deal with my life, because my life was good. It was better than good; it was great, and I was in control, right?”

Currie’s choice to trade Benzedrine for cocaine after discovering the negative effects of increasing amphetamine use on her appearance during the filming of Foxes is an excellent representation of teen logic, and sounds exactly like the inner voice of her Annie character, who flames out spectacularly, dying young and staying pretty.

While this image could be viewed as cautionary, Foxes’ aesthetic -- filmed in glowing soft-focus neon -- conjures a more glamorous effect. We revel in the foxes’ freedoms and care less about their fates. Though she ends up dead, Annie is open to adventure, encountering kindred spirits wherever she goes. Her short life looks like one long party, with the occasional bummer hangover of school administrators, parents, and, ultimately, psycho-sexual predators.

There are no down sides to Dierdre playing the field; instead, her stock just rises.

In the film’s central scene, Madge’s pretend adult dinner party at her real adult boyfriend’s house ends up crashed by teens (starting with Laura Dern’s trouble making Debbie) who completely trash the place. The party gone out of bounds resembles every parent’s worst nightmare of an unsupervised teen rager.

Nevertheless, Madge’s man forgives his jail bait love … and ends up marrying her? Admittedly, their huge age difference has aged poorly, but must have been someone’s happy ending back in 1980?!?

Finally, our protagonist, Jeanie, learns to nurture herself and leaves needy mom and flaky friends behind for college where she can finally focus on “me.”

Authentic images of late seventies reality filter through gaps in Foxes’ lurid music video fog. Gangs of teens well-versed in fending for themselves hit the streets, talking tough, and faking a worldliness that ends up becoming real.

Left to our own devices, Gen X kids experimented with sex, alcohol, and drugs in after school playgrounds. Large teenage parties took place in fields on the outskirts of town, kegs acquired who knows how. Well, everyone knew. Parents obviously coughed up the cash to inebriate teenagers who showed up for the event. (In Foxes, Madge’s mother is shocked by her own decision to buy a keg for her teenage daughter’s party.) This was considered a normal rite of passage, as long as no one got behind the wheel, which, of course, everyone did.

While they warned against drinking and driving, my parents treated my periodic hangovers as comic events. Understanding that I would find and smoke pot (this being the late seventies/early eighties), my parents rolled joints from their own stash for me to take on a Friday or Saturday night outing. The assumption was that California kids will be California kids, and besides, stories regularly circulated about teens becoming psychotic after smoking marijuana laced with angel dust (PCP). This wasn’t enabling behavior as much as it was harm prevention.

The first time I ever tried pot was December 9, 1978, when my mom passed me the end of a joint she and her best friend were sharing on our living room couch just as Saturday Night Live was coming on TV. I didn’t really feel anything, but the two women nudged each other and giggled behind my back when I went into convulsions after Dan Aykroyd’s Julia Child cut herself while boning a chicken, spouting copious amounts of blood all over her French Chef kitchen. Maybe I was high, but this skit remains one of the funniest things I have ever seen on TV, combining a spot-on impersonation with the original cast’s penchant for the absurd.

By this time, my mother had married her third husband and was settling into what would be a life-long partnership. Our former single-mom/eldest child dynamic was replaced with one that resembled a more traditional family. My step dad was a good man who really cherished my mom and rarely, if ever, had an unkind word for anyone. He was a gentle, fun-loving guy, though he came with some baggage: a complicated relationship with a volatile ex-wife, and two sons, one with personal issues that regularly disrupted the harmony of our home.

The outline of our lives was beginning to look more normal on the outside, which only increased the feeling that I didn’t belong. As a young teen, it was too late for me to give up my independence now that our household had become more secure. Though that security was truly only ever an illusion. My step dad made little working in a grocery store. My mom bounced from job to job. Both often worked swing shift (3pm to 11pm), which revived my old habits and responsibilities. They eventually lost their first house after a series of bad financial breaks and we winded up in several rental homes of varying quality while I finished high school.

Most kids entertain escape fantasies. What I felt was probably no different, except there was a part of myself that I could not allow to surface. I didn’t know, or didn’t allow myself to think that I was a gay kid. Others in that small town noticed and pointed, sometimes hissing homophobic slurs. They tried to taunt me into admitting an identity I wasn’t equipped to understand or address. I could exist undisturbed for long periods of time and then, from out of nowhere: a verbal assault designed to separate and shame. A spotlight freezing me in its glow. A call that I could not answer. Random others knew something about me that I could not allow myself to think because it was unthinkable.

I was a thought crime awaiting its thought.

The wildness continues next week. I hope.

This piece was ready to post in the usual Wednesday 6am slot, but Substack prevented publication for some unknown reason, which seems to have been resolved. Fingers crossed.

I’m so glad you’re back! I’ve missed your posts.

“The Ice Storm” is one of those films that has stuck in my mind more than most. It’s so uncomfortable and feels so authentic. Those contradictions, like Sigourney Weaver instructing Christina Ricci on appropriate behavior, make the film unique and memorable. And “Foxes,” as you point out, has similar moments of discomfort and realism. Thanks for another great essay.