Over the Edge

Blow it up. Burn it down.

Inspired by a 1973 San Francisco Examiner article titled “Mousepacks: Kids on a Crime Spree,” which reported on a juvenile crime wave in Foster City, California, a suburb south of the San Francisco airport, 1979’s Over the Edge is probably the most accurate portrait of teenage ennui ever produced. Adopting documentarian Frederick Wiseman’s direct cinema style, and using unknown and non-professional actors in the main roles, the film feels savvy and authentic.

You can really relate to the frustration the bored kids feel, faced with life in a planned community that didn’t consider their actual lives or needs in its planning. “Over the Edge may well be the first movie you’ve ever seen in which bad architecture is, if not evil, then its exemplification. The setting is New Granada, one of those tacky suburban communities that appeared all over the U.S. in an explosion of real-estate speculation and second-rate urban planning in the 60’s and early 70’s. New Granada is a complex of banal, motel-like condominiums, severely functional apartment blocks for those who cannot afford to buy the condominiums, streets that curve meaninglessly into wasteland still to be developed, and an ultra-modern high school that looks as if it had been built yesterday to house tomorrow’s robots... New Granada is a nearly perfect visual representation of the built-in obsolescence that is supposed to keep the American economy going, but which creates junk faster than the junk can be recycled. If New Granada’s kids are zonked out zombies, they are simply a little more rude and less self-satisfied than their zombielike parents.”

The teenagers have but one, sad Quonset hut recreation center to call their own, in the middle of a dirt yard sparsely populated with age-inappropriate outdoor playground equipment. Even that is poorly funded, staffed solely by Julia (Julia Pomeroy), the kids’ only real advocate, open for severely limited hours, and contested by local developers and police.

A trio of teenage boys aimlessly seeks thrills in this half-built suburb that has hit hard times. Carl (Michael Kramer) pines after Cory (Pamela Ludwig), but finds himself at odds with her sometime boyfriend Mark (Vincent Spano). Ritchie (Matt Dillon in his film debut) is a tough kid from the wrong side of the tracks who is constantly being hassled by Sgt. Doberman (Harry Northrup), a cop on a power trip who clearly hates kids. Claude (Tom Fergus) experiments with drugs to find escape.

In one of the film’s funniest scenes, Claude arrives at school believing he has taken speed in preparation for a test, but soon discovers it was acid and begins a school-day-long bad trip, forced to view Hieronymous Bosch paintings in art class. During an authentically cheesy educational film about the evils of school vandalism, he melts his own face into his hands and sighs, “so destructive.”

I am positive I went to school with this kid: the cut of his straight blond hair, the set of his jaw, the compressed shape of his vowels, the way yesterday’s trip becomes tomorrow’s story...

Over the Edge begins with wish-fulfilling mayhem when Mark and a friend shoot out the front window of a cop car from a freeway overpass and then yelp with glee as they make a clean getaway on bikes. The teens mean business in this teen movie.

As is true in The Ice Storm, Foxes, and Times Square, the parents in Over the Edge cannot hear their children. Their own desperate pursuit of an elusive good life has made them deaf to the troubles their actions are brewing in their own kids, their own homes, and the precious community they are failing to build.

Carl is engaged in an ongoing conflict with his father Fred (Andy Romano), that is unsuccessfully mediated by his mother Sandra (Ellen Geer). Fred’s Cadillac dealership is in trouble; its survival depends on a deal with a group of Texas businessmen to build an industrial park on an empty lot (originally intended as the site of a drive-in theater and bowling alley) just across from the kids’ rec center. The Texans witness a near riot there, brought on when Sgt. Doberman illegally enters the building, conducts a body search, and finds a small amount of hash in Claude’s pocket.

Carl discovers where the businessmen are staying and helps sabotage the vehicle his father loaned them. As they break off talks and leave town, one of the Texans observes: “Seems to me like you all were in such a hopped up hurry to get out of the city that you turned your kids into exactly what you were trying to get away from.” The words are too true.

The original Examiner article detailed the real troubles: “Mousepacks. Gangs of youngsters, some as young as nine, on a rampage through a suburban town. One on a bike pours gasoline from a gallon can and sets it afire. Lead pipe bombs explode in park restrooms. Spray paint and obscenities smear a shopping center wall. Two homes are set ablaze. Antennas by the hundreds are snapped off parked cars in a single night. Liquid cement clogs public sinks and water fountains. Street lights are snuffed out with BB guns so often they are no longer replaced. It sounds like the scenario for an underage Clockwork Orange, a futuristic nightmare fantasy. But all the incidents are true. They happened in Foster City where pre-teenage gangs—mousepacks—constitute one of the city’s major crime problems.”

The kids are motivated by an overwhelming boredom growing up in a world that wasn’t designed with them in mind.

Gen-Xers are often characterized as having turned thirty at age ten and then never grown any older. Left to our own devices, as we regularly were, we deployed kid logic to break up the monotony of lives that were simultaneously unstructured and over-determined. We were expected to grow up to be our parents, as they believed (not really) they had dutifully done before us. The world we were inheriting was already a mess (that would just get progressively messier, spinning further beyond our control).

Over the Edge is so satisfying because it ends with a gorgeously cathartic release of anger at the raw deal received by kids who have been ignored all their lives, told to just suck it up and go along on whatever path our parents decided (this week) was the right one.

Carl and Ritchie encounter Cory and her unnamed friend (who looks a little like The Runaways’ drummer Sandy West) leaving a house after stealing a gun and some shells. The four head over to an abandoned condo that Carl and Ritchie are using as a clubhouse, in a half-built subdivision that appears to have been put on permanent pause. Cory picks up the gun and uses it as a guitar, dancing along to Cheap Trick’s “Surrender.” (Ludwig, the actress who played Cory, is responsible for some of the film’s music choices, which she played on her boombox on set. Her boyfriend worked as a roadie for Cheap Trick before they hit the big time. This was the band’s first appearance on a major soundtrack. They hadn’t yet had a hit single.)

At the end of the scene, Cory points the gun, which she believes is empty, and fires. The gun goes off and for a moment we think Carl has been shot, which reminds us that the teens might think they are playing, but the stakes are real.

When the scene ends, the girls heading off into an empty field at dusk on the left and the boys on the right, the cinematography turns poetic. Though the setting is a suburban tract home development, brown and same and mundane, there are moments when the camera finds beauty. Huge clouds float in a dusky blue sky over a barren field of gold.

The feeling is similar to Terence Malick’s 1973 Badlands, another teen outlaw movie, which is full of gorgeous imagery contrasting the main characters’ senseless acts of violence.

More conflicts ensue, resulting in Ritchie stealing his mom’s car and heading out of town with Carl. When they are pursued by Sgt. Doberman, Carl begs Ritchie to get rid of the gun, for which they have no bullets. Ritchie ends up killed after pointing the empty pistol at the angry cop.

Carl escapes, heading back to town.

The parents hold a town meeting in the school auditorium to discuss how the teen crime wave plaguing their community is affecting property values. While the adults argue causes among themselves inside, their kids surround the building, securing the exits with bike chains, and effectively trapping their parents inside. They rampage in the parking lot, smashing windows, and setting vehicles on fire.

Kids take over the P.A. system and mock parental admonishments to do homework and practice piano. Breaking into a cop car, they discover guns and begin shooting, while panic rises inside the school. The kids blow up a generator and the lights go out. More screams from the terrorized adults. Fires break out in the building. The chaos builds and blooms into glorious release.

A teenage viewer can feel the fiery images play across the liquid surfaces of corneas, burning themselves on the retina and scrambling through the optic nerve, forever filed and endlessly interpreted somewhere inside a developing brain.

For the longest time I remembered the kids basically locking their parents inside the school auditorium and setting the building on fire. This was my dark teenage wish fulfilled, probably conflated with the prom scene from Brian DePalma’s 1976 film Carrie, wherein a prank on an endlessly bullied girl finally goes too far, resulting in the telekinetic teen killing everyone at the dance, and gorgeously exiting the high school gymnasium in slow motion, leaving the building and her tormentors engulfed in flames.

Given Over the Edge’s problematic theatrical release, I am not sure when I first encountered it.

The film received positive reviews. Roger Ebert described it as “a ragged story that ends with an improbable climax, but it’s acted so well and truly by its mostly teen-age cast that we somehow feel we’re eavesdropping... It’s about the rhythms of teen-age life, about how kids talk and feel and yearn, about the maddening sensation of occupying a body with adolescent values but adult emotions.”

Orion, the studio that distributed Over the Edge, feared the incendiary climax of their film would inspire violent outbursts similar to those which had occurred in a handful of theaters during screenings of gang-related movies, Boulevard Nights and The Warriors, released earlier that year.

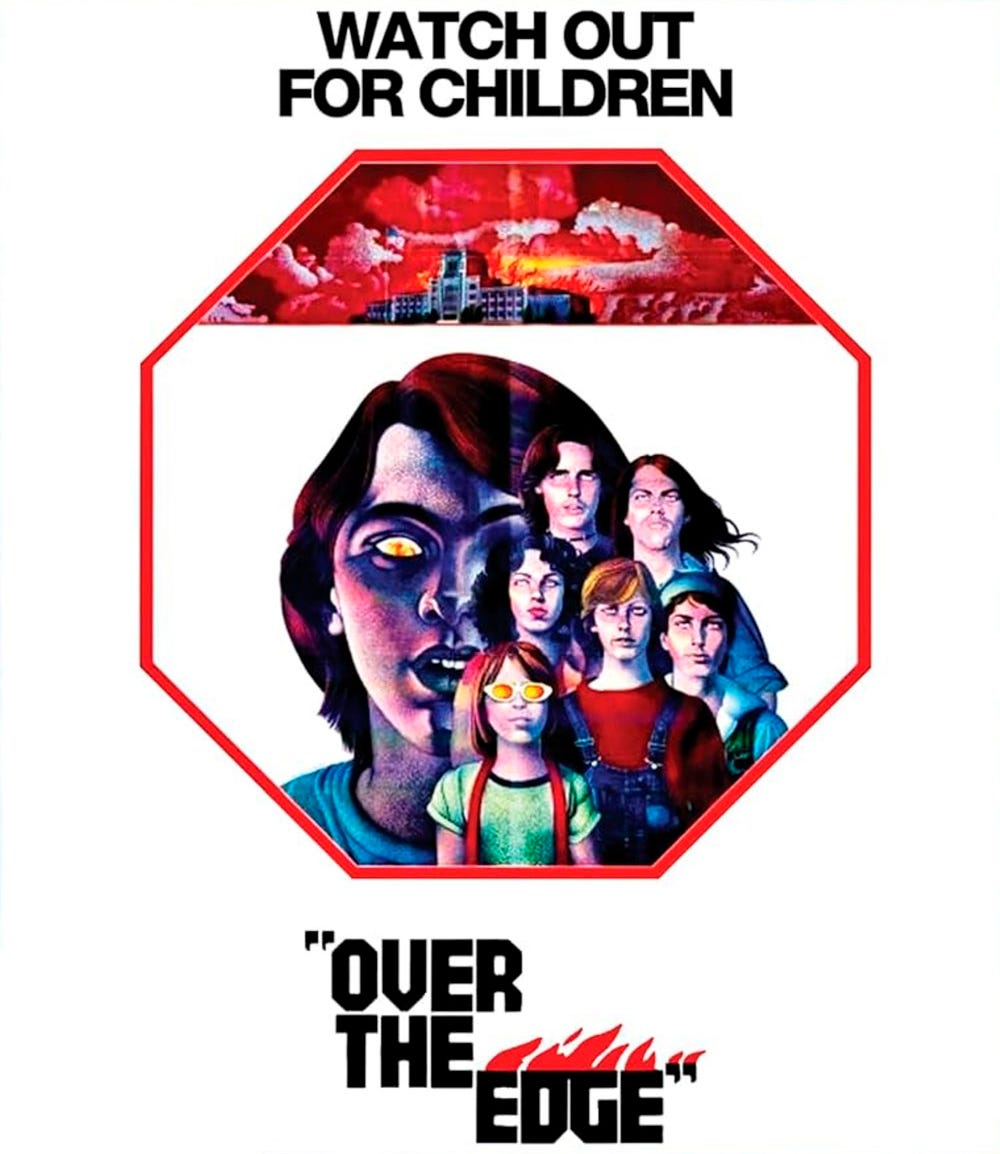

Tim Hunter, the film’s co-screenwriter remembers, “Orion didn’t want this movie to have that gang affiliation, so they marketed it as a horror film.” The poster contains the kids inside a stop sign, their eyes zombied out. An institution floats above them against a red sky. The slogan is “Watch out for the children,” and the “Edge” in the title is on fire. “And then they just dropped it. It wasn’t shown anywhere. They were afraid of copycat violence. It was hugely disappointing.”

A few years later, the movie reappeared in a series titled Word of Mouth at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater in New York, which screened films that were “worthy but -- for whatever reason -- hadn’t received good distribution”. This resulted in a mostly positive New York Times review: “A lot of Over the Edge is awkwardly acted and motivated, but it is staged with such vivid efficiency and concern that, as you watch it, you are frequently caught halfway between a giggle and a gasp.”

Perhaps the awkwardness of these teen movies is what makes them so appealing. They capture a phase of life marked by uncertainty about how to be in a developing body or how to act in increasingly complex and often highly charged situations. The fact that the characters do act, and often inappropriately, is probably intended as cautionary, but feels celebratory. A decade of pent-up emotions released in an orgy of violence; a dream of desecration (of everything a repressive society holds dear) coming intensely true.

I imagine I first saw Over the Edge on USA Network’s Night Flight, but I cannot find any evidence that this is true. This block of programming, which aired for four hours starting at 11pm on Fridays and Saturdays, included an eclectic range of materials, including music videos and cult films, through a barrage of commercials that became increasingly more frequent as night gave way to morning.

As I entered my teens, got my driver’s license and a car, it became clear that it wasn’t acceptable for me to be home on weekends. Though I most often worked as a busboy on either Friday or Saturday night -- or both, when my shift ended around 11pm, my parents silently telegraphed that I shouldn’t return home until the wee hours of the next morning. This is what “normal” teens did -- those who had friends. I wasn’t a normal teen; I didn’t really have friends until I fell in with a ramshackle and not always cohesive group of misfits, who sometimes made space for me and sometimes did not.

We met up and tried to figure out something to do on weekend nights together, most of us on the outside of whatever social events were taking place in the fields outside of town or at a private house party to which we were not invited. Often we ended up at one or another’s house stoned and watching Night Flight or SCTV until 2am the next morning.

Sometimes there were sleepovers in this co-ed group, but most often we went our separate ways.

On many nights, I just drove the town’s dark back roads on my own, pretending I had someplace to be and someone to be with, a fire in my mind incinerating the nowhere that seemed to be everywhere — like the kids who went “over the edge” and never came back.

another ode to crappy parenting.. and a chilling precursor to school shootings. like you point out at the end of your article, it's as if parents want their children to fray at the edges, combust, go wild.