Now, Voyagers

Though you may soon fade, my love for you never will.

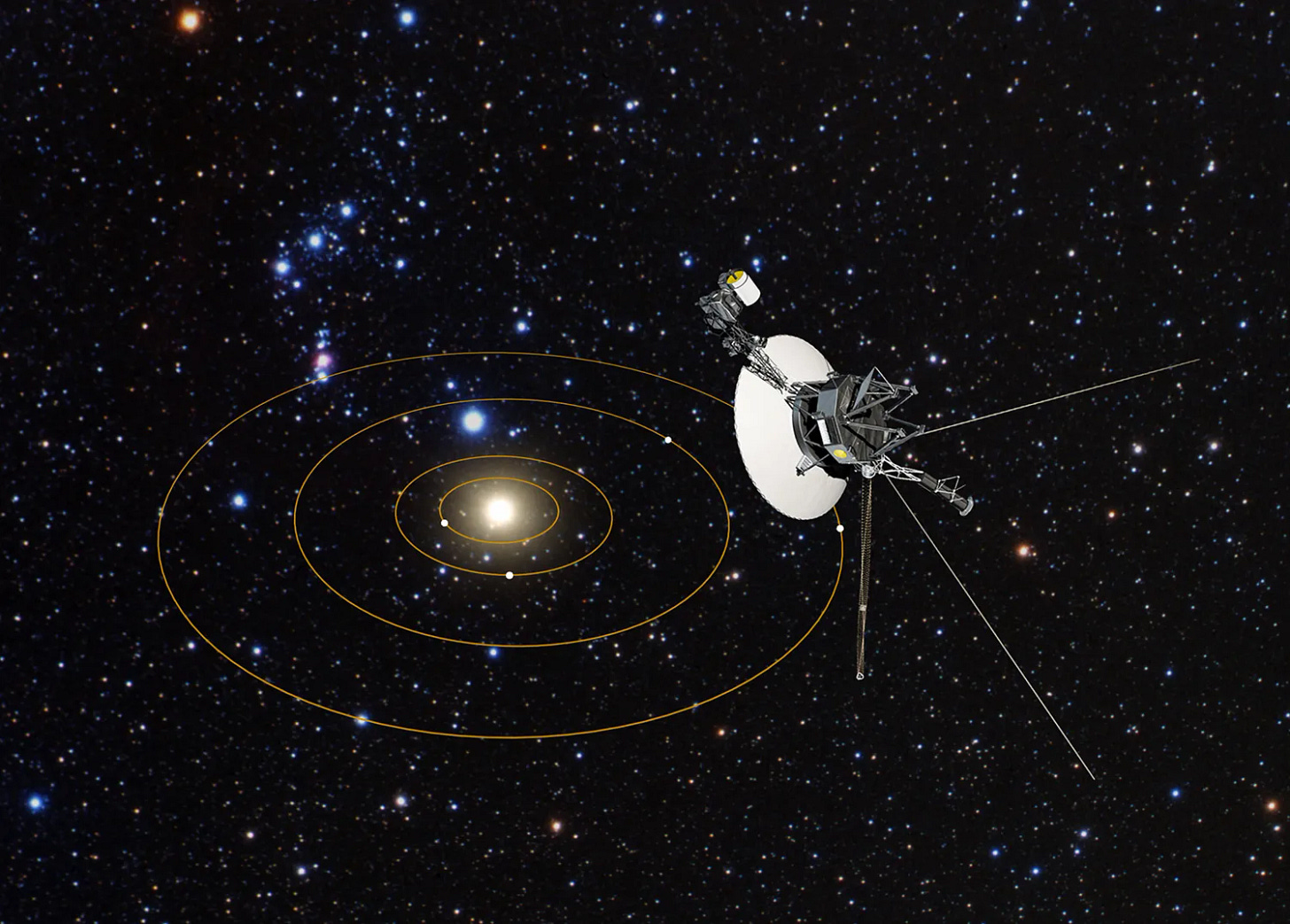

It’s odd how a crudely rendered image of heavily pixelated concentric circles, representing our solar system, inspires so much melancholy in me.

Produced in 1977 to illustrate the trajectories of “twin” spacecraft, Voyagers 1 and 2, the animation has a video game quality that begins with a god’s-eye view looking down on (at the time) nine planets circling a star. The angle changes, zooming in closer to the orbital plane to focus on the three dots closest to the sun. Two white lines zoom away from the Earth dot and head toward Jupiter. Voyager 1 gets there first at the beginning of 1979, even though it was the second of the craft to launch, flung into space on September 5, 1977, just 16 days after its sibling, which arrived at Jupiter a few months later.

Both trajectories turn sharply left, heading for the next stop on their tour of the outer solar system. At the white disc that represents Saturn, the spacecraft part company, Voyager 1 heading up and out of the ecliptic plane while Voyager 2 takes another hard left and continues toward Uranus. The line representing Voyager 1 disappears completely, leaving Voyager 2 to finish the journey alone. And I am bereft. My heart cannot disconnect from Voyager 1, which tugs me into deep space, leaving behind our solar system’s abundant mysteries for the great void between stars.

The animation slows down to indicate the huge distance between the orbits of Saturn and Uranus. This change in speed feels like a shock absorbed, the way time bends after a trauma, expressing both loss and determination — Voyager 2’s will to continue alone melodramatically coupled with its inability to quit. The machine’s stubbornness can be felt in the line that keeps moving, again veering left around the backside of Uranus, slowing even more as the spacecraft makes its way to Neptune.

When Voyager 2 reaches that planet, the animation zooms out again to depict the journey arrested at that point. The Voyagers began their adventure together, but became separated mid-stream, never to meet again, each continuing solo into the vastness of space.

This wistful video represents an adventure that continues today, while illustrating the separation of siblings. The parting feels abrupt; the action seems rash and ill-advised. Wouldn’t the two craft be safer in the unknown together?

Of course, they were never together, these pixelated white lines only make it seem that way. They were always separated by weeks, months, and now decades. They encountered the same things, visited some of the same spaces, but hung out in different neighborhoods. They were fraternal twins, programmed to see differently from the beginning, each sending separate postcards back home. But they weren’t sharing their experiences with one another.

From the start, we were encouraged to anthropomorphize this delicate pair of probes sent on a “grand tour” to visit our planet’s elder relatives in the solar system’s outer reaches. All the language surrounding the Voyagers was designed to create a strong emotional bond. It was easy to imagine them as recent Cal Tech graduates embarking on the kind of trip that once signaled a privileged coming of age — a test of self-reliance. Together, they would gain valuable knowledge and experience, see the sights, and send back impressions of ancient wonders found on roads not yet traveled.

Which is why their parting at Saturn feels so poignant. The twins, formerly united in purpose, suddenly fall out, one continuing the trip as planned, the other taking the next route to elsewhere. One can easily see how moody loner Voyager 1 might get sick of Voyager 2’s can do spirit. Voyager 1 is definitely the brunet sneaking a cigarette in the shadows of uninhabited space to Voyager 2’s blond running marathons and basking in the glow of gas giants.

Naturally, my heart belongs to Voyager 1. On its way out of the heliosphere, the stoic spacecraft was instructed to turn back and take pictures of the planets it could locate as it zoomed away. This composite is called the “Family Portrait” and features an image of Earth as a “pale blue dot” bathing in what looks like a band of sunlight. (Is it a lens flare effect of some kind?) The snapshots encourage us to see our planet as a sibling in a family of heavenly bodies, while also demonstrating our incredible smallness even within our own tiny neighborhood.

Equipped with a record player and an 8-track tape deck, like teens cruising main in hatchbacks, each Voyager points insistently at Earth while speeding away at roughly 37,000 miles per hour, a speed that will never decrease as long as space remains frictionless. Both still share their discoveries in unexplored regions, measuring energy waves and particle densities that arrive as haunting audio chirps transmitted back to eager ears.

In 2012, Voyager 1 exited the heliosphere and entered interstellar space on its way toward Gliese 445, a nearby star. It will fly relatively close to that red dwarf in about 40,000 years, provided it does not collide with any other objects as it makes its way through the Oort Cloud, a region of comets and other bodies believed to have also been ejected from our solar system.

In true “golden child” fashion, Voyager 2 is heading toward Sirius, the brightest of the stars in our nighttime sky and, barring interruption, will arrive there in roughly 296,000 years.

You can imagine them reporting back while speeding away: “Protons from the sun decreasing, I can no longer feel the tug of the sun’s gravity or the rush of solar wind at my back. Plasma increasing, a river coming from elsewhere, flowing around the heliosphere. I am swimming now in a stream of energy that crackles throughout the giant galaxy of which I am but a blip from a blip that circles another insignificant blip.”

The further the spacecraft get, the more space yawns between them. They travel away from each other and from us. They represent that part of us that wants to know, that wants to say hello, but the reality they face is the immensity of distance and its relationship to time.

Powered by plutonium-238, which has an 87.7-year half-life, it was estimated the twins had enough energy to continue communicating through 2025. Attempting to maintain contact for as long as possible, the Voyagers were instructed earlier this year to shut down most of their remaining sensors. (It takes 23 hours for signals from Earth to reach Voyager 1, which is currently 15.7 billion miles from home and is projected to be one light day (1.609 x 1010 miles) away a year from now.)

Both probes now speed functionally blind through interstellar space. Soon they will go silent, which fills me with sorrow. They are travelers in a barren landscape mumbling to themselves about the cold.

A part of me drifts in space inside of them, next to, perhaps, the romantic Golden Record that lovers Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan produced together that can, if understood and enabled, play back the sounds of 1977 Earth. I have heard snippets of this record’s actual contents — “hello” in many languages, the sound of a mother and child, wildlife and nature, folk songs and industry — but imagine instead a mixtape of pop hits from that year in its place. “Strawberry Letter 23” followed by “Flashlight,” “You Don’t Have To Be a Star,” “Sir Duke,” and “Dreams.”

The Golden Record contains the potential song the machines can sing to whoever or whatever might find them. It insists, like Dr. Seuss’ Who did for Horton, “We are Here!”

Well, we were here. By the time anyone hears our song we will be long gone. The Voyagers offer a few bits of scant evidence that we ever were.

The word “voyager” is somehow syllabically sad, calling to mind the melancholy of Now, Voyager, a 1942 movie for a Sunday afternoon. “Don’t let’s ask for the moon; we have the stars.”

The spacecraft that bear this name demonstrate the pathos of our isolation. We are stranded in a little corner of space, unable to bend the laws of physics to access other regions of even our own galaxy, much less traverse the great expanses between galaxies in the infinity of the universe.

The Voyagers generate a boundless optical zoom away from Earth, continuing outward forever. The rubber band that would draw them back grows cold and dry and cracks, releasing them from the grip in which we ourselves are trapped.

Both probes have already escaped the effects of the sun. While I contemplate this motion, I am perpetually unable to quite grasp my own smallness. I contemplate the Voyagers in the interstellar medium and my imagination balloons out to meet them. I become one of them, having separated in a huff from my twin and set my own course, not realizing that the instant I made that decision my fate was sealed. I will wander alone forever on an unknown and ultimately unknowable journey.

My power supply will dwindle and I won’t be able to sense the particles around me or swerve to avoid any obstacles that might appear. I may never meet an end, instead continuing to drift forever, which is a barely comprehensible concept. I may never halt or be halted. Once my resources are depleted, I will die a lonely death, no longer able to communicate with home.

I am momentum.

I am a love letter in search of a lover.

“See you in 296,000 years, Jeddy.”